South Asian women in Britain: Finding a voice, 40 years on

South Asian women in Britain: Finding a voice, 40 years on

“If we remember our rich collective past, we will find ourselves stronger in the battles ahead”

Gouri Sharma talks with journalist and activist Amrit Wilson, forty years after her influential feminist book Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britain.

Featured photo: Amrit Wilson speaking on behalf of Awaz at International Campaign for Abortion Rights rally, Trafalgar Square, 1980. Women of colour had insisted that the rally’s demands included the ‘right to safe contraception, freedom from forced sterilisation and similar abuses’. Credit: Michael Ann Mullen

The year was 1978 and millions of South Asians globally were facing upheaval. The ink on India’s post-Partition map was still drying, Bangladesh was now an independent nation, and Idi Amin had carried out the expulsion of thousands of Ugandan Indians. In the UK, anti-racist struggles were being waged across the country in reaction to hostile state policies and far-right violence.

It was in this context that Indian-born, British-based journalist and activist Amrit Wilson published her book, Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britain. Containing discussions and intimate one-on-one interviews with South Asian women living in the UK, it was a groundbreaking look at the struggles facing some of the country’s newest arrivals.

Its feminist approach resonated with a cross-section of Asian women – students, activists, mothers – and Wilson was awarded the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize.

“I noticed that many young South Asians had no knowledge about, or the means of finding out about these early experiences and struggles. I felt that this is a history that needs to be told and told in a way that’s accessible to everyone”

A second edition of the book, with a new chapter and preface, was released late last year, and it’s as relevant today as it was forty years ago. As one commentator wrote, “Finding a Voice remains an influential feminist book, exploring what it was like to be a migrant, a worker, and a woman straddled between two cultures in Britain.”

Wilson, now 78 years-old, said that the reasons behind the republishing were primarily two-fold. “Looking at the way the authoritarian state has grown, and how much the 1970s were a crucible for it, made me think that it would be worth republishing. Also I noticed that many young South Asians had no knowledge about, or the means of finding out about these early experiences and struggles. I felt that this is a history that needs to be told and told in a way that’s accessible to everyone.”

March: ‘Black People Against State Brutality’ national demonstration, 1979. The photo was among a selection included in the second edition of “Finding a Voice”. Credit: Michael Ann Mullen

Republished by Daraja Press, a not-for-profit publisher that ‘seeks to contribute to reclaiming the past, contesting the present and inventing the future’, the book reveals the stories and feelings of the women and girls who we see so often but don’t always notice – for example the hijab-wearing giggling schoolgirls, the Gujarati grandmother praying at the temple or the Bengali aunty on the bus.

It’s their voices – via interviews conducted in Hindi, Bengali, Urdu and English – that we hear, yet it’s not just about us listening. Wilson shows us the historical, cultural and political contexts in which these voices exist, exploring the feudal system back in their countries of origin, the racism and misogyny of the British state and society, workplace exploitation, sisterhood and marriage, to name a few. Originally released just 31 years after Partition, it also served as an in-depth look at women’s lives so soon after the trauma of that period.

“Not one of the women spoke to me about Partition but some of those women had probably gone through two very traumatic upheavals and perhaps that’s what made the second upheaval so painful. When they talked about loneliness or missing home or their sisters, it was possibly made more intense by the fact that they or their mothers had experienced similar trauma, or perhaps even worse trauma, when Partition occurred,” she said.

The new chapter, ‘In Conversation with Finding a Voice – 40 years on’, is a selection of short essays by a range of young women who read or re-read the book in the last year and tell their own stories weaving them around those of the women in the book. It is a section Wilson says she is excited about. What do the women from the first edition think of the reissue?

“There has been such a huge change in South Asian communities so many women don’t know.” she says. “Some of the older women, those from Pakistan, for example, have gone back there, while others have passed away.

“What I find with many of the Gujarati Hindu women, particularly those who were workers at the time, is that they don’t want to remember those days of struggle. I’ve met young women whose aunts may have been in strikes which they know nothing about. Part of the reason could be that people want to simply move on, but it could also be because they have moved up in class and are embarrassed by the past.”

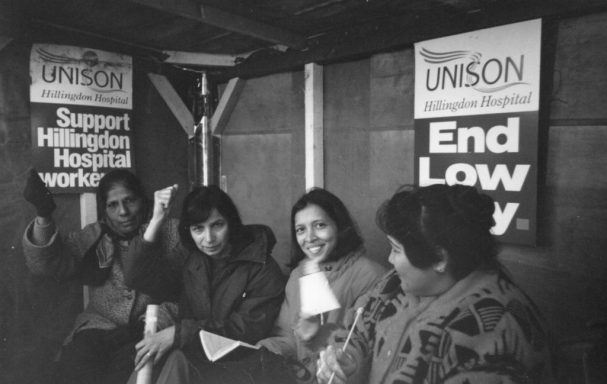

Hillingdon hospital strikers in 1997. The strike had been underway for two years after workers were sacked for refusing a pay cut. Wilson looks at worker strikes in the book. Credit: Sarbjit Johal

Throughout her career, Wilson has written extensively on race and gender in Britain and South Asia, and has been actively engaged in political struggles. She is a founder member of South Asia Solidarity Group, the Freedom Without Fear Platform and Awaz, and was till recently a board member of Imkaan, a Black, South Asian and minority ethnic women’s organisation dedicated to combating violence against women in Britain. Her reflections on the struggles South Asian women still face, the steps they are taking and the challenges that stand in their way are included in the new edition.

Patriarchy and “honour” are also discussed in detail and Wilson tells us these issues are more complex now. “Earlier on it was something that was essentially feudal and many aspects of that patriarchy came from our countries of origin. When our communities were first established in this country, patriarchal boundaries which women were not supposed to cross were set up too and if they did, they would face dire consequences”.

“What the Grunwick strike established was that it was possible for low-paid workers to fight back very effectively. Today, as before, we are up against not only the state and employers, and sometimes the ultra-right who support the employers, but also the racism of the unions and their reluctance to take up low-paid workers’ issues”

“Today things have changed. Although you still do find cases of women being killed and izzat (honour) is mentioned, you do not, on the face of it, see that very stark feudal patriarchy within communities as frequently as before. It’s more that it has become incorporated into the interstices of British capitalism, with things like huge dowries, the corporatisation of weddings and the market telling women what they should look like. So we never got rid of the patriarchal system that existed before, it’s just been absorbed into a broader structure of capitalist patriarchy.”

In the book she looks at worker strikes like Grunwick in 1978 and the Imperial Typewriters strike in Leicester four years earlier. The issue of migrant workers, she says, remains particularly important today.

“What the Grunwick strike established was that it was possible for low-paid workers to fight back very effectively. Today, as before, we are up against not only the state and employers, and sometimes the ultra-right who support the employers, but also the racism of the unions and their reluctance to take up low-paid workers’ issues. In response, low-paid workers of today in the gig economy are setting up their own independent unions which are actually winning strikes, and this is extremely inspiring.”

Laxmiben Patel was a striker at the Grunwick Photo Processing Plant. Here, she looks at the unveiling of a mural commemorating that strike. Credit: Pete Webster

As for fighting racism and Islamophobia she feels that the current climate of fear, is having an impact on this. “’The so-called War on Terror and the Hostile Environment Policy has meant that Muslims are being targeted and arrested on the most trivial of pretexts. It has created an atmosphere of fear in the communities and as a result it shifts the whole way people think of organising.”

Within South Asian communities, she also notes a change. “When I wrote the book back in the late seventies, Hindus and Muslim women in Britain interacted without distrust . Today, Islamophobia of the state and media have served to create so many barriers between Hindus and Muslims . In addition there is the Hindu supremacist government of the BJP in India which fuels further divisions in Britain – I don’t know if Muslim women who didn’t know me would speak to me so openly today”.

“A way to resolve this is for younger people to aspire to some kind of unity, across language, religion and caste – simply as South Asians and I’m hoping that my book can encourage such discussions of unity”

“I have to say, though women’s groups based on black feminism are far less divided in this respect and I think this is because ‘black feminism’ is by its very nature intersectional.”

To move forward then, what does she suggest we do to bridge these divisions, essentially so we can fight back against some of the bigger forces that continue to oppress us?

“A way to resolve this is for younger people to aspire to some kind of unity, across language, religion and caste – simply as South Asians and I’m hoping that my book can encourage such discussions of unity.”

It’s also worth, as she writes in the new introduction, to go back: “If we remember our rich collective past, we will find ourselves stronger in the battles ahead.”

Book launch photo: Some of the nearly 200 women who attended the London book launch of Finding a Voice and came to the front at the end to celebrate with Amrit. Credit: Keval Bharadia

‘Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britain – second edition‘ is available for purchase via the Daraja Press website.

Comments (0)