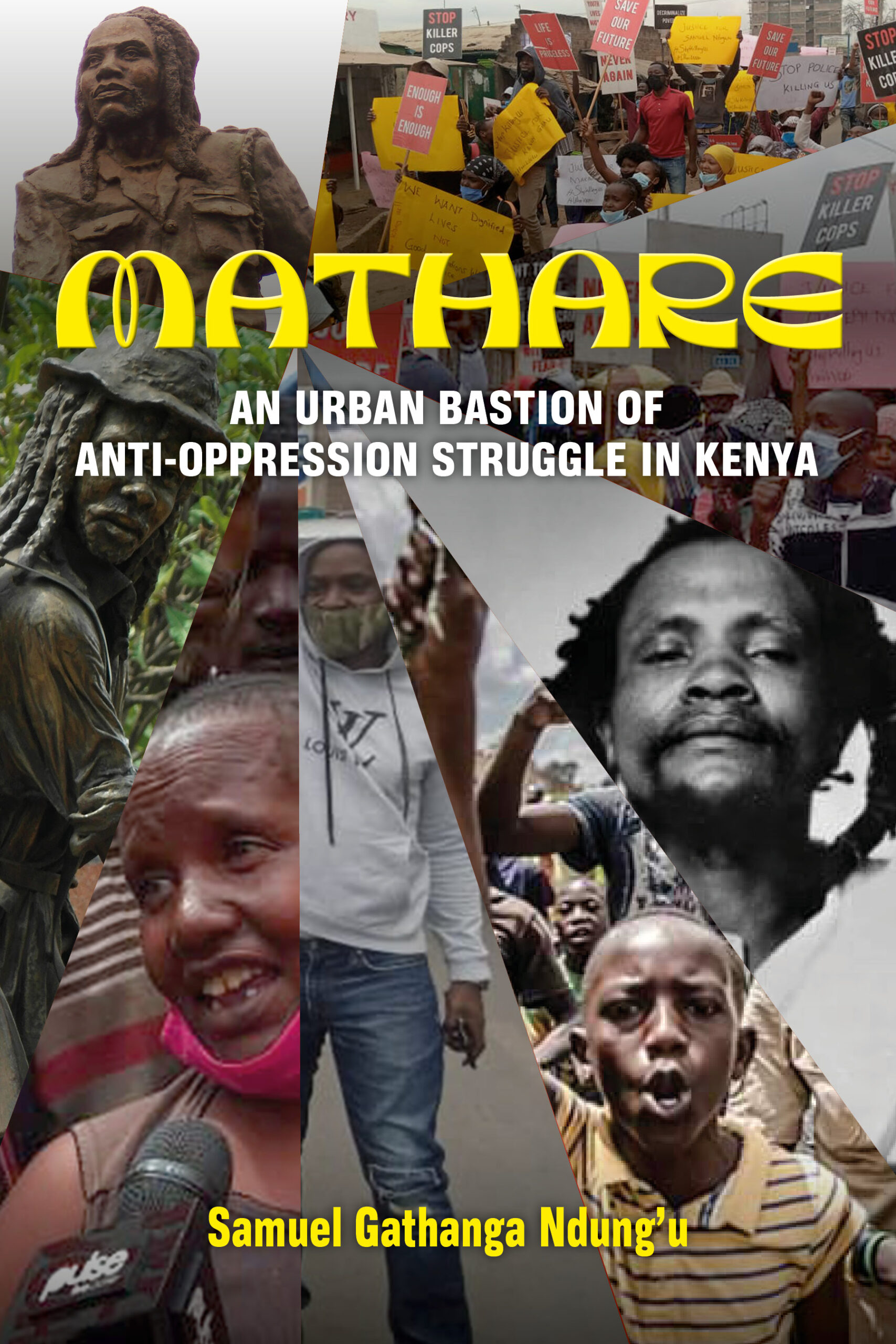

Book Review: Mathare: An Urban Bastion of Anti-Oppression Struggle in Kenya

Written by Wairimu Gathimba, a member of Mathare Social Justice Centre and Organic Intellectuals Network ([email protected])

The Kenyan education system fights against memory, against acknowledging our past. But we need to recognize our pasts to grieve them, and in doing this work, we must tell these stories ourselves. For a long time, most of the narratives we have had about ourselves and our histories have either been the sanitized narratives of the neo-colonial state or the white-washed versions given by our colonial masters, and a lot has been lost in these versions. The stories we tell ourselves shape our esteem, decisions, and ultimately our destiny. Thus, we must revisit our histories and uncover the various hidden truths that have long been buried. The past is all pervasive- we cannot escape it. It is part of who we are; our cultures, our behaviours, and manifests in all aspects of our day-to-day living. Knowing our true history connects us to our past and tap into a dimension of longitudinal meaning over time. Because of this, learning our true history is essential; history gives the past and the present visible form and meaning. In doing this, history also allows us to see into the future by offering precedents for current behavior and forewarning us from repeating previous mistakes. But in a neoliberal education system, education is framed around investments in students as human capital, and the value of education is tied to the student’s prospects for future earnings. Such a limited approach to education raises concerns about the purpose of education and the relationship between schools, state governance, and democratic life. Beyond education, neoliberal governance also results in the privatization of other public institutions and processes including urban planning. Harvey (1989) famously abstracted the spread of neoliberalism into urban planning as a shift from urban managerialism to urban entrepreneurialism. Whereas managerial cities had been primarily concerned with providing services and facilities to the urban population by the local administration, entrepreneurial cities in an era of increased interurban competition, had to focus on attracting investment and employment more than ever before. The consequent de-democratization of urban policies has left out a big chunk of the urban population from decision-making processes. This population continues to be threatened by unaffordable urban developments in the form of evictions and neglect. It is against this backdrop that Mathare, the urban bastion of the anti-oppression struggle in Kenya, exists.

Despite its role in the fight for Kenya’s independence and the post-colonial struggles for liberation, Mathare’s story is often overlooked. As Gathanga writes in his book, most people outside the settlement associate the name Mathare with the mental hospital bordering the settlement. For others, their narrative of Mathare is one of pity, considering that the place is known to house the urban poor. But Gathanga’s story of Mathare is different. As he writes, this book is a counter-narrative of Mathare and one written from a proud insider perspective. It is refreshing to have a retelling of Mathare’s story, especially one from an insider’s view. When people tell their own stories, they get to rewrite their history, and this is evident in Gathanga’s book. Getting to tell our own stories also moves us from the objects of our story to the subjects. It prevents us from being othered in our history. Gathanga’s book offers the untold story of Mathare, one of Nairobi’s most significant informal settlements, unraveling the role of Mathare in the fight for Kenya’s independence and the subsequent betrayals and delayed promises of the post-colonial regimes. The book starts by highlighting Mathare’s role in the colonial struggle as a place where returning Kenyan soldiers would settle after finding their lands grabbed. With the knowledge and skills they gained from fighting in the war, these soldiers organized and operated the Kenya Land and Freedom Army. The colonial administration razed houses in Mathare after learning that Mathare was serving as a Maumau base. Yet this did not deter the residents and only emboldened them. This spirit of resistance and defiance would come to define Mathare, even in post-colonial administrations. Despite their contribution to the fight for independence, Jomo Kenyatta’s neo-colonial regime overlooked Mathare’s residents and their needs. This was despite the increase in population in the slum in that period as people moved from rural areas to seek jobs in the towns now that the new post-independent government had abolished Kipande zoning system. Like his predecessor, Moi ignored the fate of those living in Mathare and other urban informal settlements. Then Mwai Kibaki came into power after 24 years of Moi’s iron-fist rule, and like the majority of Kenyans, the residents of Mathare were hopeful of the new democratic regime. However, this regime was defined by delayed promises and, even worse, the 2007/2008 post-election violence clashes, which disproportionately affected the urban poor, including those in Mathare. As Gathanga writes, persistent structural issues such as unequal distribution of resources coupled with the immediate electoral fraud acted as triggers for violence. The state responded with even more violence that was especially targeted at young men in the slums. Surviving this harsh reality as they always had, residents came together to sneak out and hide young men amongst them. As Gathanga writes towards the end of the first chapter, “It is this togetherness that had always defined the people of Mathare whenever crisis struck.” Uhuru Kenyatta’s administration featured great economic plunder that exacerbated the already precarious situation in Mathare. As with all regimes defined by the entrepreneurial urban governance that accompanies neoliberalism, Uhuru’s government pursued developments that often had the informal sector and the urban poor at the periphery of their agenda. Demolitions, even those done for the community’s “benefit” were done inhumanely and led to suffering, pain, and loss of property. Yet despite all this, Mathare continues to survive and act as an urban bastion of the anti-oppression struggle. It is also in Mathare that the social justice movement was birthed, with Mathare Social Justice Center opening its doors in 2015. From a single centre, this movement has grown to over 26 community centers, all working under the Social Justice Centres Working Group. Once again, Mathare has faithfully risen to the occasion to serve as a voice of courage and hope in a time of crisis. It is this beautiful story that Gathanga documents so well. This book is the narrative of a community’s resilience in the face of the betrayals and violence of the Kenyan state against it. It is a story of survival and people fighting together against a failed system. The book deftly captures Mathare’s legacy of resistance and is packed with details highlighting the role of Mathare in the first, second and third liberations of Kenya. It is a radical must-read for all that sheds light on this largely forgotten history of organizing and resistance played by Mathare.

Vinci

October 28, 2022This review definitely makes me want to read it