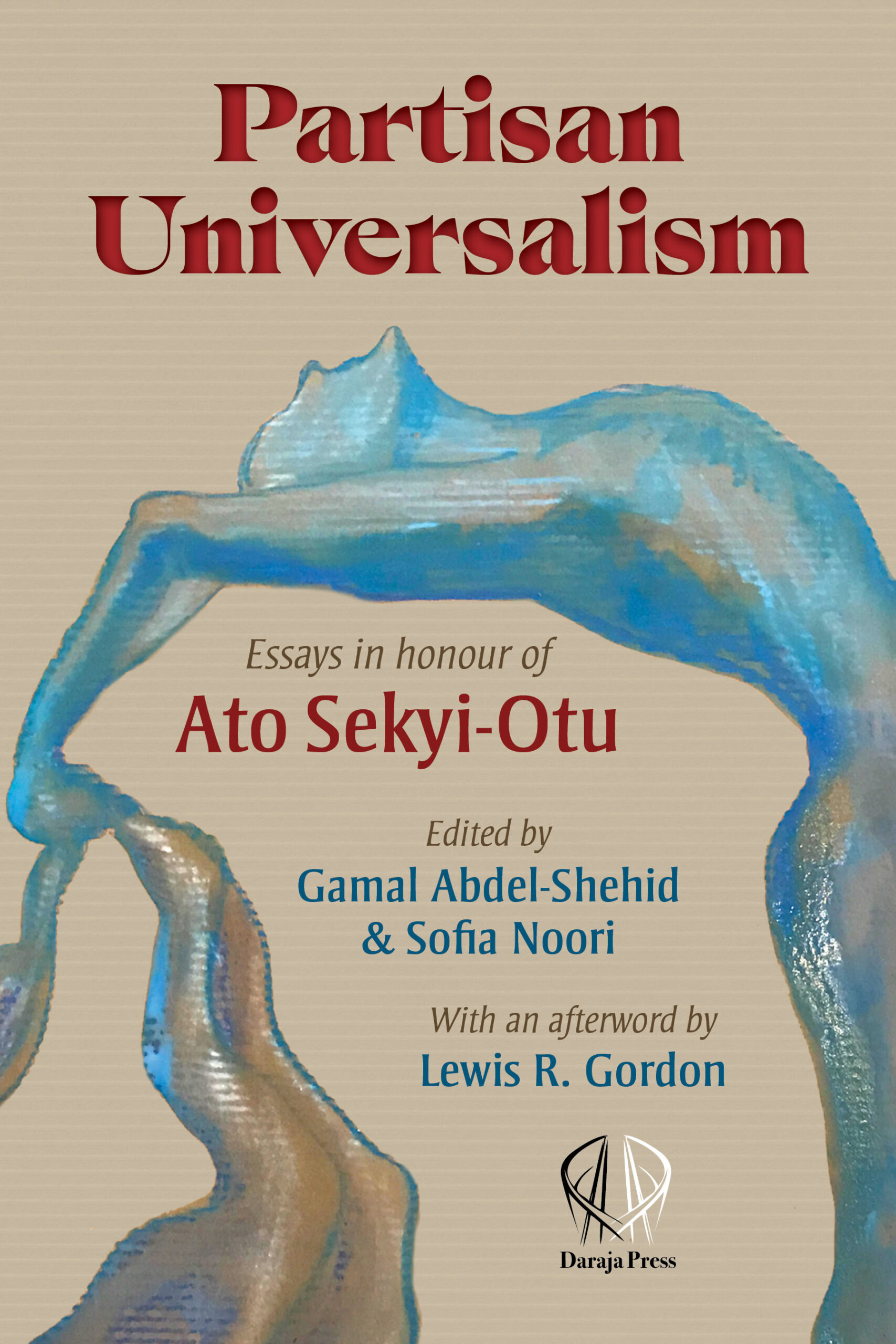

Book launch: Partisan Universalism: Essays in Honour of Ato Sekyi-Otu

Join us for a discussion celebrating the life and work of Ato Sekyi-Otu, Professor Emeritus in the Department of Social Science and the Graduate Programme in Social and Political Thought at York University in Toronto, and author of Fanon’s Dialectic of Experience (1996) and Left Universalism, Africacentric Essays (2019). The panel will be hosted by Gamal Abdel-Shehid, co-editor of Partisan Universalism together with Sofia Noori. Contributors to the volume include Christopher Balcom, Susan Dianne Brophy, Nergis Canefe, Tyler Gasteiger, Nigel C Gibson, Jeremy M Glick, Stefan Kipfer, Sophie McCall, Esteve Morera, Jeff Noonan, Patrick Taylor, Olúfémi Taiwò and Lewis Gordon. It is hoped that all contributors will be able to join the discussion.

This event was moderated by Lewis Gordon.

This is the text of Ato Skyi-Otu’s remarks:

PARTISAN UNIVERSALISM

TALK AT BOOK LAUNCH

SATURDAY 18 DECEMBER, 2021

Dear Friends,

This is a truly extraordinary day. I am enormously grateful and honoured to all of you for the extraordinary essays you contributed to Partisan Universalism and for participating in this event. I must say a very special thank you to Gamal, Sophia and Firoze for crafting this project and bringing it to fruition. Jane Anna Gordon’s extremely generous blurb calls the book and your contributions a celebration of my work and the person I am. I am of course grateful for that encomium. But I’d like to think that it is also a celebration of the twin vital principles and practices of individuality and connectedness made beautifully manifest in your essays.

I thought of beginning my remarks today by singing a famous tune. But for fear of inflicting on you an inauspicious start to our conversation, I will rather just echo the opening line of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s plea for understanding fundamentals, understanding the fundamentals of their fundamental project: “All we are saying is…” I will not dwell on the substantive content of that plea: “Give Peace A Chance.” For one thing, we who want to see this wicked world destroyed, comprehensively destroyed, cannot be fetishists of peace unmodified. What interests me is Yoko and John’s invitation to get the basic meaning of their project right. So let it be with what we left universalists mean to say. All we are saying is this: Our objections and protests as sentient beings against injury and our proposals and projects for change, whether they are reformist or reparative or revolutionary, harbour an appeal to universality, an appeal that may be avowed and explicit or merely latent and implicit but is most certainly unavoidable. A critical, even insurgent universality, to echo Massimiliano Tomba, as thought and practice, haunts and drives the languages of discontent. The protagonist in South African writer Bessie Head’s novel Maru asks: “How universal is the language of oppression?” All we are adding to that rhetorical question is: “How universal is the language of discontent and protest and revolt”? To the Afropessimist argument that “grammars of suffering” are distinct and resist mutual translation; to the thesis that the “Black grammar of suffering” is radically different and irreducible to any other grammar of suffering, certainly to the humanist narrative of suffering and redemption, we say with Fanon, Afropessimism’s putative ancestor and uncooperative witness, we say with Fanon: “All forms of exploitation are alike… All forms of exploitation are identical, for they are all directed at the same ‘object’: the human being.” And we say that that thesis of radical particularity is contestable and is contested not only on the part of external critics waiving the cosmopolitan flag or by native converts to an exogenous Enlightenment. It is internally, essentially contestable on indigenous discursive terms. All we are saying is that the most local, context-specific, particularistic protests against injury and proposal for redress ground their claims inescapably in a humanist universalism. Such, we argue, is the latent universalism of Black Lives Matter. That tacit universalism survives the strategic separatism adopted by some of the movement’s protagonists who insisted, for example, that sympathetic white demonstrators take a back seat. And it survives and must survive thanks to the only coherent non-tautological answer to the following question: Do Black Lives Matter because they are Black, or do they matter because they are human? We know the stakes that come with giving the only coherent answer: “Black lives matter because they are human lives.” That answer runs the risk of being invoked to defang the rhetoric of resistance by transmuting its insurgent partisanship into the syrupy generality of “All Lives Matter.” That is one possible use or rather misuse of the latent humanism of BLM, appropriation by a disingenuous and reactionary a-racialism that denies the specific gravity of the Black condition and the specific urgency of the demands made in its name. Not unlike what rightwing Machiavellians do with Martin Luther King’s prophetic demand, “Not by the colour of their skin,” twisting it into a history-amnesiac descriptive egalitarianism and a “you are on your own, baby” individualism in order to discredit affirmative action and other restitutive or reparative programmes. But consider another appropriation in which universalist humanism, rather than displacing the idiom of Blackness collaborates with the latter, so that the two are conjointly retained and deployed otherwise. I am referring to the 2020 explosion of demonstrations in Nigeria, which began as protests against the brutal violence of a state apparatus, The Special Anti-Robbery Squad and then aimed their discontent at socioeconomic inequalities. Some of the demonstrators marched under the banner #NIGERIAN LIVES MATTER, but also under the banner #BLACK LIVES MATTER EVERYWHERE. This, in a country which is virtually all-Black and for that very reason does not normally call its citizens Black, a context, that is to say, where the principal contradiction is not Black lives in relation to white supremacy and its repressive practices. Under these circumstances why would the protestors invoke BLM not indeed as a literal assimilation but as an analogical identification, why would they do that, were it not for the latent universalism that motivates BLM itself, sparks its discontent and justifies its demands and aims in the first place – in spite of the relativist self-understanding and separatist temptations of some of its protagonists?

Today more than ever, the necessity of the appeal to the universal as an internal weapon of criticism and justification, making that appeal explicit, is not a matter of theory. As we gather here, a vicious bill called “Draft Bill for the Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values” is before Ghana’s Parliament. It calls for the criminalization of the practice of homosexuality and even advocacy of the rights of homosexuals. Quite frankly the bill licences persecution. With impeccable logic the Speaker of Parliament intones: “We will not legislate to infringe on the Human Rights of people, but we will legislate to ensure that culture and traditions are not violated.” What our “culture and traditons” are, what makes them praiseworthy, and how we promote them, all that is evidently exempt from the province of Human Rights. A prominent Catholic Archbishop concurs. He accuses supporters of gay rights of being under the spell of postmodernist subjectivism and relativism, but then offers as an argument against gay rights the claim that they are imcompatible with Christianity and Ghanaian culture. Is that the best argument you can offer, Holy Father, this quintessential resort to relativism, to the claims of a particular religious and cultural tradition, more precisely and worse still, to a particular interpretation of those traditions, the unholy idolarous bow to the forcible triumph of one interpretation? Is that the best you can do, Catholic prelate of all people, putative votary of the whole? Tell us Holy Father: the Christian values and Ghanaian traditions in the name of which you support the draconian bill before Parliament, are they good and praiseworthy simply because they are Christian and allegedly all our own?

There is a widespread intolerance and moral panic in the land, instigated by the religious and secular elites and supported by large sections of the people, designed to deflect their revulsion with and revolt against miserable conditions of existence. Against this moral tyranny dressed up as cultural piety, this talibanism without the Taliban, only the appeal to the universal, one that asks in a native idiom “Are we not also human beings?”, only that appeal can protect and even save lives. Human lives in their protean incarnations.

“It is a matter of unleashing the human being.” Thus spoke the young

Fanon. Let the human be. Let it be. That is all that we are saying.

Ato Sekyi-Otu

Comments (0)